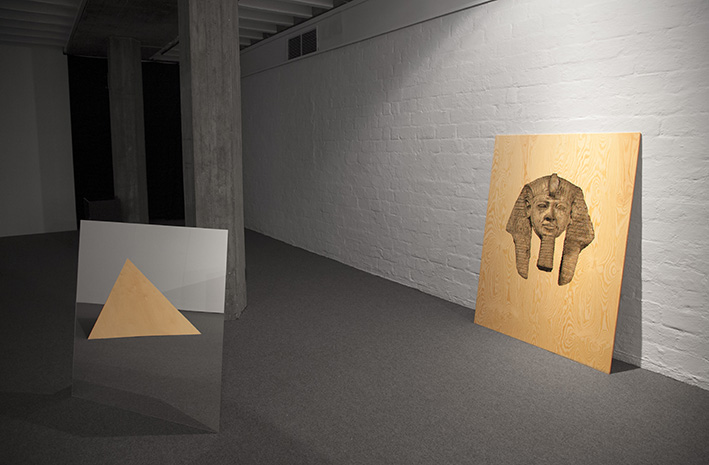

PYRAMIDION – 2011

Prints of heads of historical figures who have been subject to post-mortem decapitation to various degrees. They consist of two prints of Haydn's head (grave robbing for the purpose of phrenology) on glass, three prints of Mata Hari's head (scientific study for the purpose of phrenology) on paper in red, green and blue, respectively, and three prints of Ramses II's head (faulty mummification leading to a broken neck) on plywood.

HAYDN, MATA HARI & RAMSES II

The Austrian composer – Joseph Haydn (1732-1809 AD), the Dutch exotic dancer – Mata Hari (1876-1917 AD), and the Egyptian Pharaoh – Ramses II (1303-1213 BC) shared a common destiny after their deaths – their bodies had all been subject to post-mortem decapitations. The head of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II had probably been dislodged by accident in the process of mummification, which can be detected by scans that show how a piece of wood is holding the mummy’s head in place. Haydn’s head, however, had been stolen by enthusiasts of phrenology – the pseudo-science of measuring skulls – shortly after his death in 1809. The thieves were thereby able to analyse the shape of his head and to measure its contours for signs of musicality. For this purpose Haydn’s head was to remain separated from his body until it both were transferred to his tomb in 1954.

As for Mata Hari, her body had found its way at the Museum of Anatomy in Paris after she had been shot for treason in 1917 during World War I. Her body was preserved for scientific study in a collection constituted by notorious criminals at a time when phrenology still made decapitation a fashionable pursuit toward those who had no one to claim their corpses. But when it came down to close the museum, it was found that the head of Mata Hari had gone missing and its whereabouts remains a mystery to this very day. The mystery is comparable with history’s inability to come to a conclusion about the mind that once animated the object. The evidence, however, suggests that the dancer had been subject to a set-up by a double agent on the French side of the spy network.

The beheadings of these corpses expresses a paradoxical fetish by those attempting to analyze the thoughts that once filled them. It is the awkward paradox of matter for a head to becomes a metaphor for thought while having simultaneously been displaced form the body it once ruled. What, after all, is there to be learned of criminality by looking at the disembodied head of spy? How does the ‘musical bump’ in Haydn’s skull explain lyrical genius? And what is it about the Pharaoh’s body that insists it remains whole when his spirit crosses the thresholds of the afterlife? The exercise of measuring, observing and embalming comes to embody thought that had been stripped of the mystical properties of consciousness and laid bare to the instruments of science in their attempts to dissect matter. But the end outcome only goes to illustrate a logic by which the device for measurement had become interchangeable with its concept of itself in the act of measuring.